1IN3 Podcast Ep.011: Meeting the needs of male victims of domestic and family violence - Part 3

This is a broadcast of a Panel Session called Meeting the needs of male victims of domestic and family violence, presented at the Australian Institute of Criminology's Meeting the needs of victims of crime conference held in Sydney on 19 May 2011.

Part 3 of the Panel Session features Greg Andresen, researcher and media liaison with Men's Health Australia, presenting a paper called Meeting the needs of male victims of family violence and their children.

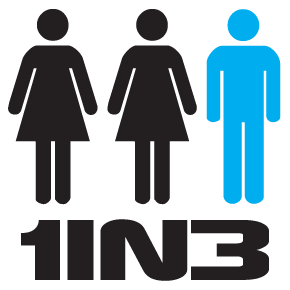

Contrary to common beliefs, around one in three victims of family violence and abuse is male. While many services and community education programmes have quite rightly been established over the past four decades to support female victims of family violence, the needs of male victims remain largely unmet. Male victims of family violence and their children are one of the most underserved populations of victims of crime in Australia, with appropriate and tailored services being almost non-existent. This paper will present a brief overview of what is required to meet the needs of Australian male victims of family violence and their children. It will:

Present the often unheard voices of male victims of family violence and their children

Describe the specific experiences of male victims of family violence and their children (barriers to disclosing and finding support; different forms of abuse; impacts upon victims and their children)

Review the scant support currently available in Australia for male victims of family violence and their children

Outline the support required in order for the needs of male victims of family violence and their children to be met

Discuss recent overseas and Australian support initiatives for male victims of family violence and their children that could be adopted more broadly.

Download PowerPoint | Watch presentation

Elizabeth Celi: Greg Andresen has been working in the field of men’s health and wellbeing since 2004, both in Adelaide and in Sydney. He currently works as a researcher and a media liaison for Men’s Health Australia and as senior researcher for the One in Three Campaign which Greg will certainly give you a bit more information about. So please welcome Greg up.

Greg Andresen: Thanks very much Elizabeth. I’ll start by talking a little bit about the organisations that I work for. Men’s Health Australia is a website that’s been running since 2007. It’s Australia’s primary source of information about the psychosocial well-being of men and boys. The One in Three Campaign was launched about 18 months ago. I’m Senior Researcher with the campaign. The aim of the campaign is to raise public awareness of the existence and needs of male victims of family violence and abuse.

What am I going to cover today? Often when this area is discussed – the area of domestic and family violence – people get lost in facts and statistics and numbers. I really wanted to let the voices of male victims and their children come through in this presentation – the human beings that are experiencing these dreadful situations. I’m going to look at the specific experiences of male victims and their children. Look at what’s happening overseas – there’s some really great initiatives that are happening overseas in terms of specific support initiatives for men and their children. I’m going to look at what’s currently happening here in Australia – what’s available. And then outline what we think is required in order to truly meet the needs of this group of victims of crime.

I’m not going to talk about violence against women today. I’m merely talking about male victims of family violence because they are an underserved population that unfortunately receives scant attention. What we believe is that both genders need and deserve appropriate support and especially, I think we’d all agree, the number one point is if we care about stopping children from being exposed to violence, we need to focus on both men and women.

I’m not going to be talking about intimate partner violence like Toni – I’m going to be talking about broader family violence. Of course that includes intimate partner abuse from current and ex-partners, both straight and gay, but it also includes often ignored victims of broader family violence: parents, step-parents, children, uncles, aunts, etc. Often when family violence is discussed, people assume we’re talking about intimate partner violence, but we really want to include all of those family relationships.

I’m going to start by playing a short two-minute news report from the UK that interviews a couple of male victims just to give you some of the voices of those men and what they’ve been through.

[VIDEO]

Reporter: The majority of domestic violence is committed by men against women. But now, an increasing number of male victims are coming forward. Men who are more aware of the help available and are more prepared to talk about the issue. The Montgomeryshire Family Crisis Centre in Wales is one place which provides a refuge. This victim escaped from his partner a month ago, fleeing with their three children after years of mental and physical abuse.

Male 1: I was threatened very aggressively by complete strangers that she had invited into the house. Alienated me from my family and my friends. I felt like I had nowhere else to go. I literally felt like I was trapped in there.

Reporter: This victim is one of the centre’s success stories. He’s now in his own home and has custody of his daughter after three-and-a-half years of violence from his alcoholic partner.

Male 2: I would be asleep, she would come upstairs after she’d been out and the next thing I know I’ve got a fist being put in my face and things like that you know and that’s how the violence would erupt. The lowest point was when, you know, the baby was say a year old, the knives and things like that started coming out. I honestly believed she was going to kill me, I really did.

Reporter: But not all men find it easy to call for help.

Male 1: I don’t feel like a man because of what’s been done to me and what I feel I allowed to be done to me.

Reporter: While centres like this are doing good work, the challenge now is getting society to recognise men too can be victims of domestic abuse. Jonathan Samuels, Five News.

[END VIDEO]

Greg Andresen: You can really see from those interviews some of the issues that are faced by men when they are in this situation. There was a great qualitative study done by researchers in W.A. last year called Intimate Partner Abuse of Men, and it found that abuse of men really takes the same forms as it does against women. It involves a pattern of controlling behaviour and often involves multiple different forms of abuse, but it can really include the spectrum of abusive behaviours that we are all familiar with in the literature: physical violence, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, etc. The researchers also identified what they termed Legal-Administrative abuse, which is the use of legitimate services in a way that abuses the rights of the victim. For example, taking out a false restraining order to prevent the victim having access to his children.

Now, on the right-hand side [of the slide] here in the blue boxes, I’ve put up some more quotes from men. These have come from the research literature or they have been left on the One in Three website. Read them if you’re comfortable with them, but once again, I really wanted those men’s voices to come through.

The impacts of family violence upon male victims. Obviously, there’s fear and loss of feelings of safety. That can be challenging for many men because they’re often raised to feel that they shouldn’t feel scared. And so to admit that fear is very challenging for many men. Feelings of guilt and shame is another big one. Once again, if men are raised to feel that they as men should be strong and tough and independent, there’s a lot of guilt or shame in admitting the fact that they are being abused.

Feelings of helplessness – we saw that in the video we just watched – the man feeling like he was literally trapped and had nowhere to go. Difficulties with trust, anxiety, stress, flashbacks. Unresolved anger is a big issue. Loneliness and isolation is huge for men who are victims of social abuse and isolation. They really can lose all contact with friends and family and that’s especially debilitating for them because they feel they have nowhere to turn.

Mental health impacts... there’s a good quote there at the top, this man really feels like his life is crushed and he has really lost his dignity. Low self-esteem and/or self-hatred is another big one. There’s another good quote there from Kevin feeling vile and dirty, not only because of what had happened to him, but what he feels society says about what’s happened to him.

And at the severe end of the spectrum we have depression, suicidal ideation, self-harm and attempted suicide. We have a number of stories that men have left on the One in Three Campaign website about their attempts to take their own lives.

Impaired self concept: once again it’s that challenge to the sense of manhood that male victims can go through. If men are raised to feel that they’re supposed to be able to deal with whatever is thrown at them and to take it on the chin, that can get… as this guy says, “It can get pretty heavy to carry around.”

Physical injuries, illness and disability, obviously, and especially when weapons are used. Use of alcohol and other substances to self-medicate. Sexual issues. Loss of work can be a big issue. Just like with women, a lot of men who are severely abused really can no longer function in the workplace and so, for example, this guy Robin here ended up on a disability pension.

Loss of home is another one. Often if men leave the situation that they’re in, they will have to start again. As do women, of course. This was the situation that was faced by Tad here. Loss of relationships with friends and family – once again, that’s that social isolation.

Then there are the issues to fathers around their children. Many men fear that if they leave the situation they may not have access to their children – they may lose contact with their children – so many men stay for that reason. And many men have a protective instinct – they wouldn’t want to leave because their children will be left with the abuser and so they stay in the abusive situation in order to be able to protect their kids.

And lastly, in terms of the impacts on the men themselves, some violence against women campaigns, by suggesting that men are the only perpetrators and females are the only victims of family violence, this can actually re-victimise men who watch these campaigns and increase their feelings of helplessness, isolation, low self-esteem, depression, anger and that loss of manhood. There’s a good quote there by Peter about how him and his boys feel whenever they see those ads.

Impacts on the children of male victims: the literature is quite clear that it doesn’t matter if it’s mum hitting dad or dad hitting mum or another family relationship, if children are witnessing violence in the family, that’s abusive to the children and could cause them long term harm. And of course many children will also experience direct violence and abuse themselves.

The long-term impacts on children include immediate impacts on their behavioural, cognitive and emotional functioning, their social development, and long-term harm to their education and employment prospects.

There was a good study done, the National Crime Prevention Study – a survey of 5,000 young people nationwide – which found that in terms of predicting whether children who were exposed to violence would grow up to either be perpetrators or victims, the best predictor of perpetration was witnessing certain types of female-to-male violence. Witnessing mum hit dad was the best predictor for children growing up to use violence. The best predictor of victimisation was witnessing male to female violence. So if we’re going to break this cycle of violence, we really need to say, ‘no’ equally to violence against women and men so that boys and girls don’t grow up to either perpetrate or be victims themselves.

I’m briefly going to look at the barriers to male victims disclosing their abuse. Like women, men face a lot of barriers to disclosing their abuse. However, men face a set of unique barriers which make them much less likely than women to report: about a third to half as likely to report being a victim. I’ve grouped them into two basic areas: external barriers refers to the fact that many barriers are created or amplified by the lack of public acknowledgement that males can also be victims and also the lack of appropriate services out there for men. Men may not know where to seek help, they may not know how to seek help, they may feel there is nowhere to escape to, they may feel they won’t be believed or understood. If they do seek help, they may feel that their experiences may be minimised or they may be blamed for the abuse. They may fear they may be falsely arrested if they call the police because they’re the man and in that case, the children will be left unprotected.

Under internal barriers, once again, it’s those challenges to their sense of manhood. Because men are raised to feel that they should be independent and strong and be able to protect themselves, there’s a lot of shame and embarrassment about disclosing. There’s the social stigma of being unable to protect themselves. There’s the fear of being laughed at or ridiculed. The fear of being seen as weak or wimpy. And a lot of men will actually be in disbelief or denial of what’s happening to them or make excuses for it.

What’s happening overseas? There’s been some really good work done in Western countries overseas that we’re aware of. There are now dedicated telephone support lines for male victims of family violence in the UK, Ireland, the U.S. and Canada. For example, The Men’s Advice Line in the UK. There are some great printed and electronic resources available now which are available on the web to anyone in the world, for example, The Greater London Domestic Violence Project has a great booklet called, For Men Affected by Domestic Violence, and the Alberta Children’s Services in Canada put out a booklet called, Men Abused by Women in Intimate Relationships. These are great resources that men around the world can draw from.

There are a number of charities and support groups in the UK, Ireland, U.S. and Canada and India, for example, the Mankind Initiative in the UK. There’s some great community awareness campaigns especially in the UK. The National Centre for Domestic Violence, which is the main organisation around the issue of domestic violence in the UK, ran Male Domestic Violence Awareness Week in 2010 with lots of TV ads and media attention to the issue. And there’s an example there [on the slide] of a Scottish police campaign that was run at Christmas in 2009 with some male faces on it.

There are shelters for men and their children now in the UK, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark and New Zealand. For example, in Holland, Stichting Wende provides shelters in the four largest cities of Holland – government funded shelters – and all of those are currently full. And in the U.S., it’s not so much that there are shelters specifically for men and their children, but a number of women’s shelters have started taking on men and their children as well, for example, WEAVE in Sacramento County. And recently the Parliament in Taiwan changed laws so that welfare aid – financial aid – was available to male victims as well as female victims.

So that’s what’s happening overseas. What’s happening in Australia? There’s a fair amount of generic support available that both men and women can access: police, ambulance, legal aid, etc. However, generic support is often unaware of the unique issues faced by male victims because of the silence around this issue. So they are often unable to offer effective or appropriate help. And at the worst, some generic services may not believe men when they disclose, they may minimise their experiences or even blame them for the abuse.

And the Western Australian Research done last year surveyed about 200 service providers around Australia and they rated themselves and their agencies as only moderately effective in overcoming those barriers to men disclosing, so there’s a lot of work to be done.

What I’ve done here [on the slide] – I’m not expecting you to read this tiny font – but I basically went to the main domestic violence websites around Australia in all the states and territories and listed all of the services that they referred to there. So that’s a snapshot of what’s available in Australia today.

The boxes in pink are women’s only services. So men, unfortunately, can’t access them. So we can remove them from the chart. The boxes in grey are the generic services I was talking about. It’s really a lucky dip as to whether men who approach those services get the appropriate support that they need. Another issue is that individual workers in generic services may be aware of these issues and may have training and appropriate skills, but their workplace cultures often don’t support them. So let’s remove those generic services.

What we have left are male-friendly services that are set up for men, but some of these don’t specialise in issues of family violence – they may support men around relationship breakdown or other issues. So, let’s remove those.

This is what we’re left with [on the slide] in terms of tailored, specific resources supporting male victims of family violence in Australia. So what do we have? Mensline Australia – the national telephone counselling line. Recently, the Federal Government committed three-quarters of a million dollars for them to train their counsellors to support male victims of family violence. That’s the first federal funding for male victims that we are aware of in Australian history. However, we don’t know if the funding has been allocated or who will be conducting the training or how appropriate it will be. Also, Mensline is often the only port of call for many men, especially in regional areas, because Mensline is a referral service and there’s often no services for Mensline to refer the men on to. And until the One in Three Campaign launched 18 months ago, Mensline only provided resources for male perpetrators, not for male victims. So it’s only recently that they’ve taken this issue on.

Men in Queensland are particularly lucky. They’ve got their own Mensline telephone counselling service. There’s also a court support service supporting men through the court process in Queensland. There’s a small service in the Hunter Valley that was established a year ago, maybe two years ago, to support male victims. Since the beginning of this year, police in Windsor in Northern Sydney have been referring men to the Hawkesbury District Health Service for counselling.

There are some great individual counselling services and practices like Toni’s and Elizabeth’s, but they can be harder for men to find, and sometimes harder for men to afford. And the last three dot points there [on the slide] are all websites. It’s great to have websites out there, but they’re no substitute for face-to-face services.

In terms of professional development for workers in the sector, Greg’s going to talk about his program after me, so I’ll leave that to him. That’s the only training program we are aware of.

So, what is required to meet the needs of this group of victims of crime? The Western Australian Report from last year had four key recommendations. One is government-funded public awareness campaigns to raise community awareness for this issue – that it can happen to men. And they were really, really clear to say, these campaigns need to be very carefully designed so as to complement campaigns that are stopping violence against women and not damage the effectiveness of those campaigns. So we want to support men and women here. It’s not a competition.

The second point was to consider providing a range of publicly-funded services specifically for male victims. So, that would be a similar range of services that are available to women. Examples would be counselling, helplines, crisis response, community education programs, specialist services for different sections of the male population – gay men, Aboriginal men, CALD men, etc, financial support, legal advice. The full spectrum of services. They’re not recommending that as many services would be available for men as for women, but a similar range, so at least there are some services there for men to access. Also perpetrator programs for women which are relatively absent, and health service screening tools. In a number of states, when women come in contact with health services, they have a compulsory screening tool to see whether they have experienced domestic violence. Men aren’t screened at all and so men often fall through the gaps there.

The third recommendation is to consider how services for men could be integrated with women’s services and generic services. Obviously, some services would be able to be integrated and others may have to stay gender specific.

The fourth recommendation was for training for workers in the sector especially around dismantling those barriers to men disclosing so men can actually come forward and tell their stories in confidence that they’re going to be trusted and supported and their experiences won’t be denied, minimised or questioned.

What else? We’d also recommend MP’s and public servants need training because they’re the ones who are writing the laws and rolling out the programs that unfortunately have excluded men in the past. Men need to be included in the National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and Their Children and all the systemic reforms that are rolling out across the country. At the moment, it’s acknowledged that men can be victims, but basically that’s it. They haven’t been included in any other way.

We need better ABS and other data. The upcoming Personal Safety Survey is the gold standard of research in the country in terms of a broad community survey. There’s a new survey being planned for 2013 and it’s going to have three times the women’s sample compared to men, so the data on male victimisation is not going to be as good as for women.

Finally, we need tertiary education courses so people who are going into social work, health and other human services actually get good training so that they have the skills to support men when they are working in their professional roles.

My contact details are there [on the slide] and I’ll hand it back to you, Elizabeth. Thank you.

Elizabeth Celi: Thanks very much Greg. If we can give Greg a round of applause please. It’s his second presentation. I think he’s done a fabulous job of pulling together a whole bunch of information. And obviously in terms of looking at methodological considerations and the unique experiences of men, whilst some of their abuse may be similar to the levels of abuse women may experience, there are certainly some unique experiences from the masculinity perspective, so please prepare your questions for Greg.