This is a reply to a comment left by Dr Michael Flood on the News page of the One in Three website under Bettina Arndt's article "Silent Victims".

Dr Flood's comment was as follows:

Bettina Arndt refers to a mistaken statistic in a report I co-authored, “An Assault on our Future: the impact of violence on young people and their relationships”, published by the White Ribbon Foundation in 2009 (http://www.whiteribbon.org.au/uploads/media/Research_series/An_assault_on_our_future_FULL_Flood__Fergus_2010.pdf).

True, there was an error in one of the many statistics in the original report, and this was corrected as soon as it was known. The error was compounded when that statistic was used, among others, in the media release. The report was a major review of research on young people’s experiences of violence, drawing on over 150 published works and citing a wide range of statistics. One statistic was written up incorrectly, and it does not substantially alter the conclusions of the report, but it was an embarrassing error.

The original version of the report stated, “Males are more likely than females to agree with statements condoning violence such as … ‘when a guy hits a girl it’s not really a big deal’ (31%, versus 19% for females)”. This was in error. I had taken notes on the National Crime Prevention’s report “Young People & Domestic Violence” (2001), and I had mistakenly transposed 'girl' and 'guy' for this particular statement. The statement with which these young people agreed was in fact ‘when a girl hits a guy it’s not really a big deal’.

However, two things are important here. First, while this statement cannot be used to show males’ tolerance for violence against females, other statistics cited from that same study do show this. For example, the same report documented that:

14% of young males, but only 3% of females, agreed that ‘It’s okay for a boy to make a girl have sex with him if she has flirted with him or led him on.’ 15% of males (but only 4% of females) agreed that ‘it is okay to put pressure on a girl to have sex but not to physically force her’. 32% of males, compared to 24% of females, agreed that ‘most physical violence occurs in dating because a partner provoked it’. 7% of males, and only 2% of females, agreed that ‘it’s alright for a guy to hit his girlfriend if she makes him look stupid in front of his mates’.

Second, the above statement shows that just as males are more tolerant than females of violence against females, they are also more tolerant of females’ violence against males. A greater proportion of young men than young women agree that ‘when a girl hits a guy it’s not really a big deal’.

In any case, this initial mistake did not take away from the main messages of the report: that young people are exposed to violence in their families and relationships at disturbingly high levels, that this violence has profound and long-lasting effects, that violence is sustained in part by some young people’s violence-supportive attitudes, that young males have more violence-supportive attitudes than young females, and that prevention efforts can stop this violence from occurring and continuing.

Sincerely,

Michael Flood.

Thank you for your comment, Michael.

The error referred to by Bettina Arndt was unfortunately not by any means the only error to be found in your Assault on our Future report.

The report claimed to study the affects of domestic violence upon young people, but in reality only cited statistics on male perpetration and female victimisation. In that sense it fits perfectly with the general points Bettina’s article made about the misinformation about domestic violence that has been fed to the public by interest groups for decades.

The main message of your report was not about ‘young people being exposed to violence in their families and relationships at disturbingly high levels’: it was about girls and young women being so exposed. Young men and boys’ victimisation levels were intentionally omitted from the report, even though they were present in the source data.

For example:

|

Claims made in White Ribbon Report |

Facts obtained directly from source data |

|

“One in four 12-20 year-old Australians surveyed was aware of domestic violence against their mothers or step-mothers by their fathers or step-fathers” |

23% of young people aged 12 to 20 years had witnessed physical domestic violence by a male parent against a female parent and 22% had witnessed physical domestic violence by a female parent against a male parent. |

|

“Young men who have experienced domestic violence are more likely to perpetrate violence in their own relationships, although the majority do not.” |

Witnessing domestic violence was the strongest predictor of subsequent perpetration by young people. The best predictor of perpetration was witnessing certain types of female to male violence. |

|

“While physical aggression by both males and females is relatively common in young people’s relationships, young women face particularly high risks of violence and are more likely to be physically injured.” |

Males (4%) were twice as likely as females (2%) to be physically hurt. |

|

“among children and young people there is already some degree of tolerance for violence against girls and women.” |

Among children and young people there is a greater degree of tolerance for violence by girls and violence against boys (see below). |

|

“One in four (23.4%) reported having witnessed an act of physical violence by their father or step-father against their mother or step-mother (this included throwing things at her, hitting her, or using a knife or a gun against her, as well as threats and attempts to do these things).” |

22.1% reported having witnessed an act of physical violence by their mother or step-mother against their father or step-father. 17% reported seeing him throwing things at her and 17% reported seeing her throwing things at him. 14% reported seeing him hitting her (even though she didn't hit him) and 9% reported seeing her hitting him (even though he didn't hit her). 3% reported seeing him use a knife or fire a gun and 3% reported seeing her use a knife or fire a gun. |

|

“Over half (58%) had witnessed their father or stepfather yell loudly at their mother/step mother.” |

Over half (55%) had witnessed their mother or stepmother yell loudly at their father/stepfather. |

|

“31 per cent had witnessed him put her down or humiliate her.” |

22 per cent had witnessed her put him down or humiliate him. |

|

“11 per cent had seen their father/or step-father prevent their mother or step-mother from seeing her family or friends.” |

6 per cent had seen their mother/or step-mother prevent their father or step-father from seeing his family or friends. |

|

“it is known that violence against women contributes more to ill-health, disability and death in women aged 15-44 than any other risk factor, including smoking and obesity (VicHealth 2004). It results not only in immediate physical injury, but also in long-term mental health problems such as depression and anxiety.” |

The authors of the VicHealth study cited were at pains to point out that "a cross-sectional analysis is a weak design to examine the relationship between a risk factor and disease outcomes because it cannot indicate whether exposure to the risk factor preceded the health outcome, a necessary condition to prove causality." Just 0.7% of the burden of disease from intimate partner violence came from physical injury. While it is highly likely that victims of violence do go onto develop mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, it is also highly likely that individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions find themselves in circumstances where such victimisation occurs. Last year’s report from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health said the following: “Women in their 20s and 30s who report intimate partner violence experience poorer mental health prior to intimate partner violence, suggesting an inter-connected relationship; that is, intimate partner violence affects mental health status and likewise mental health affects intimate partner violence.” |

|

"this same survey also documents strong contrasts in females’ and males’ use and experiences of violence. Females were more likely to slap, whereas males were more likely to put down or humiliate, try to control the victim physically and to throw, smash, hit or kick something.” |

Females were more likely to slap (21% vs 12%) and kick, bite or hit (13% vs 11%). Males were more likely to put down or humiliate (39% vs 29%), try to control the victim physically (25% vs 11%) and to throw, smash, hit or kick something (23% vs 14%). Many forms of conflict/violence - including many at the severe end of the spectrum - were experienced at similar rates by males and females (e.g. ‘threw something at you’, ‘kicked, bit or hit you’, ‘hit, or tried to hit you with something’, ‘beat you up’, ‘threatened you with a knife or gun’, ‘used a knife or fired a gun’, and ‘physically forced you to have sex’). |

|

“Among girls who have ever had sex, 30.2 per cent of Year 10 girls and 26.6 per cent of Year 12 girls have ever experienced unwanted sex” |

Among boys who have ever had sex, 22.6 per cent of Year 10 boys and 23.8 per cent of Year 12 boys have ever experienced unwanted sex. |

|

“six per cent [of girls] said a boyfriend had physically forced them to have sex.” |

Five per cent of boys said a girlfriend had physically forced them to have sex. |

|

“the National Crime Prevention survey found that three per cent of males said a partner had tried to force them to have sex (compared to 14 per cent among females)” |

The National Crime Prevention survey found that seven per cent of males said a partner had tried to force them to have sex (compared to 14 per cent among females). |

With regard to the specific statistics cited by you:

One in three boys (33%) believe that ‘most physical violence occurs in dating because a partner provoked it’, compared to 25% of girls.

This statement does not talk about the acceptability or otherwise of violence, only the perceived causes of it.

15 per cent of males (but only 4% of females) agree that ‘It is okay to put pressure on a girl to have sex but not to physically force her’.

Over one in eight boys (12%) believe that ‘it is okay for a boy to make a girl have sex, if she’s flirted with him, or led him on’, compared to only 3% of girls.

7% of males (but only 2% of females) agree that ‘it’s alright for a guy to hit his girlfriend if she makes him look stupid in front of his mates’.

Because these questions weren’t asked in the reverse (e.g. ‘do you believe that it is okay for a girl to make a boy have sex, if he’s flirted with her, or led her on’), we don’t actually know what young people’s tolerance is of specific types of female-to-male violence.

It is true that young males do appear to have more violence‐supportive attitudes than young females. This is not surprising in a culture where men are raised to carry out all of the pro-social violent roles such as front line military, police, security officers, etc, in order to protect women, children, other men, property and social order. Boys are also more likely than girls to have been victims of violence in general (e.g. bullying, punch-ups, drunken fights, racial violence), so may well become desensitised to it.

However we find such evidence far less important than crucial evidence in the source data showing that young people’s tolerance of female violence against males is much higher than their tolerance of male violence against females - evidence completely omitted from your report. For example:

young people were more likely to say a woman is right to, or has good reason to, respond to a situation by hitting (68%), than a man in the same situation (49%)

while males hitting females was seen, by virtually all young people surveyed, to be unacceptable, it appeared to be quite acceptable for a girl to hit a boy. 25 per cent of young people agreed with the statement “When girl hits a guy, it’s really not a big deal’’.

Female to male violence was not only viewed light-heartedly, it was also seen as (virtually) acceptable. On reflection, both genders agreed that this constituted a double standard, and that it was not acceptable — really. But there was no censure, and a good deal of hilarity generated by discussion of the topic in the female groups. In the male groups, acceptability was implied through their beliefs that there was no need to retaliate to female violence in any way.

“there was no spontaneous recognition that verbal abuse or a female hitting her boyfriend could also constitute dating violence... However... these were among the prevalent forms of ‘violence’ occurring”. “Acts by females of slapping, pushing or kicking their boyfriends were widespread. However, this was not described or seen as ‘violence’ by the majority of male or female participants.”

With dating violence, ‘punching’ or ‘slapping’ your boyfriend to ‘get him in order’ was not seen as constituting violence. The key factor behind the use of ‘violence’ by females towards males was, primarily, one of an expression of frustration or anger: hence, reacting to being ‘out of control’ and needing to ‘get his attention’, ‘to make him listen’ or ‘to stop him behaving badly’. Neither males nor females indicated that males were likely to retaliate, suggesting that both groups viewed this kind of ‘violence’ as a bit of a joke. It was not something to be taken seriously.

Guys deserve it’. Both sexes supported this point of view, which was based on the idea that ‘guys stuff up’, ‘guys can be majorly stupid’, ‘guys don’t listen so you have to get their attention’. Males appeared to agree with the perceived wisdom of society (and certainly of females) that they are ‘not as good at relationships’ as the females.

The Assault on our Future report also ignored source data on the prevalence and damage caused by witnessing mutual violence by their parents/step-parents. Much more common and damaging than either male-to-female or female-to-male unilateral violence was mutual (or reciprocal) couple violence. When looking at the effects of young people witnessing domestic violence, the source data was unequivocal: “the most severe disruption on all available indicators occurred in households where couple violence was reported.”

Considering physical violence only, nearly a third (31.2%) of young people had witnessed one of the following: a male carer being violent towards his female partner; a female carer being violent to her male partner; or both carers being violent.

14.4% of young people reported that this violence was perpetrated both by the male against the female and the female against the male. 9.0% reported that violence was perpetrated against their mother by her male partner but that she was not violent towards him. 7.8% reported that violence was perpetrated against their father by his female partner but that he was not violent towards her.

It is quite disingenuous for you to claim in an almost gender-neutral fashion that the main messages of the report were that “young people are exposed to violence in their families and relationships at disturbingly high levels, that this violence has profound and long-lasting effects, that violence is sustained in part by some young people’s violence-supportive attitudes, that young males have more violence-supportive attitudes than young females, and that prevention efforts can stop this violence from occurring and continuing.”

A more accurate assessment of the main messages of the report would be that girls and young women are exposed to violence in their families and relationships at disturbingly high levels, that this violence has profound and long-lasting effects, that violence against girls and women is sustained in part by some boys’ and young men’s violence-supportive attitudes, that young males have more violence-supportive attitudes than young females, and that prevention efforts can stop violence by men and boys against women and girls from occurring and continuing.

The only way the report was able to reach these conclusions was by intentionally ignoring any source data on female perpetration and male victimisation. It’s no-wonder the report wasn’t peer-reviewed. With such biases and misinformation, it would likely never have passed.

The Assault on our Future report is not the only material of yours that suffers from these problems. Over the period June to December 2012, you presented variations upon a seminar paper, “He Hits, She Hits: Assessing debates regarding men’s and women’s experiences of domestic violence,” at a number of Australian Universities.

The paper made a number of defamatory claims about the One in Three Campaign and other men’s health organisations that are completely false and unable to be substantiated. You even failed to follow basic academic practice of citing evidence and providing a list of references so that the evidence could be checked.

We encourage scholars such as yourself to continue healthy debate about the epidemiology, aetiology, and solutions to the serious problem of domestic and family violence. It is through such debate that we progress our knowledge base and reach real and lasting solutions.

However, such debate when conducted by Senior Academics must follow accepted academic practice of attacking ideas, evidence and arguments rather than making false and unsubstantiated ad hominem attacks. It must also follow accepted academic practice of citing evidence and providing a list of verifiable references. Lastly, it must acknowledge all the source data rather than cherry-picking statistics to suit an agenda.

Kind regards,

Greg Andresen

Senior Researcher

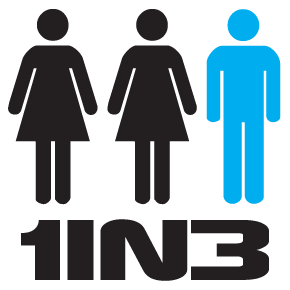

One in Three Campaign