KEY FACTS AND STATS

At least one in three victims of family violence is male

Women and men are just as likely to report experiencing emotional abuse by a partner

One male is a victim of domestic homicide every 8 days

The vast majority (94%) of perpetrators of intimate partner violence against males are female

Other family members who perpetrate violence against males are more likely to be male than female

Men in same-sex relationships are just as likely as straight men to experience intimate partner violence

Almost one in four young people are aware of their mum/stepmum hitting their dad/stepdad

Male and female victims of reported domestic assault receive very similar numbers and types of injuries

Males and females are just as likely to engage in coercive controlling behaviours

Males make up around one third of persons applying for protection orders in the three largest states

Men who have experienced partner violence are 2 to 3 times more likely than women to have never told anybody about it

Post-separation, fathers make up the majority of parents who report experiencing the highest levels of severity of fear, control and coercion.

Between 2005 and 2016, the proportion of men reporting violence in the last year from their current partners rose more than five-fold while the proportion experiencing emotional abuse more than doubled.

LATEST DATA FROM THE ABS AND AIC

Click here to view our infographic outlining the latest national family violence and domestic homicide statistics.

REFERENCED OVERVIEW OF RECENT FAMILY VIOLENCE RESEARCH FINDINGS

Contrary to common beliefs at least one in three victims of family violence and abuse is male. When reading the following quantitative statistics it should be remembered that family violence is extremely complex and doesn't just boil down to ‘who does what to whom and how badly’. The context of the violence and abuse is extremely important. Abuse can occur without the use or threat of physical violence. Please refer to our frequently asked questions page for a more detailed and nuanced analysis of family violence and abuse.

A new report from The Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health has found that almost one in three men report having experienced Intimate Partner Violence (emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse). The use of intimate partner violence among Australian men (2025)45 found that a full 30.9% of men surveyed in 2022 reported experiencing IPV in their lifetimes. Unfortunately the data is buried in the fine print of the report (Table S4 on page 87 of the Supplementary Materials).

A study published in the Medical Journal of Australia surveyed 8503 people aged 16 years or older, of whom 7022 had been in intimate relationships. The prevalence of intimate partner violence in Australia - a national survey (2025)44, had the aim of estimating the prevalence in Australia of intimate partner violence, each intimate partner violence type, and multitype intimate partner violence, overall and by gender, age group, and sexual orientation.

When it looked at the lifetime experience of any intimate partner violence among the 6934 women and men respondents with intimate partners at any time since age 16 years, it found that 45.5% of people who had experienced violence were male. That’s almost half - much higher than the one in three figure consistently found in the ABS Personal Safety Survey for many years now.

When it came to physical intimate partner violence, men made up 44% of the men and women who had experienced it. Similar figures were found for psychological violence, with 44.8% being men. Men made up a smaller percentage (18%) of those men and women who had experienced sexual violence, but in the 16-24 year age group, one quarter (24.8%) were men.

Men were about as likely as women to be victims of many types of intimate partner violence. For example:

- Hit you with a fist or object, or kick or bite you (50.4% of persons who had experienced this were men)

- Harass you by phone, text, email or social media (44.8% of persons who had experienced this were men)

- Try to convince your family, children or friends that you were crazy, or try to turn them against you (44.6% of persons who had experienced this were men)

- Keep you from seeing or talking to your family or friends (43.7% of persons who had experienced this were men)

- Use or threaten to use a knife, gun or other weapon to harm you (42.6% of persons who had experienced this were men)

- Tell you that you were crazy, stupid or not good enough (42.4% of persons who had experienced this were men).

The Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, 2022 (2023)43 found that almost one in two victims of FDV related homicide (47% or 64 victims) were male.

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, NSW Crime Tool (2023)41 found that one in three victims (33%) of Domestic Assault from January 2021 to December 2022 were male. There were 11,881 male and 24,070 female victims.

The ANROWS Research Report, Adolescent family violence in Australia (2022)40 found that a larger proportion of adolescent females than males reported using violence in the home. Specifically, 23 per cent (n=762) of females had used violence, compared to 14 per cent (n=234) of males. This difference was statistically significant. Adolescent females were statistically more likely to report that they had perpetrated both physical/sexual violence and non-physical forms of abuse against their family members compared to males (38% vs. 29%). Female young people were statistically more likely to use violence against multiple family members than males (46% vs. 38%). While mothers were more likely targets of this violence (including adopted mothers; 51%) than fathers (including adopted fathers; 37%), much of the violence was retaliatory in nature, with 68 per cent of respondents whose mothers had been violent towards them saying they had used violence against them.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2021 (2022)39 found that in 2021, males comprised just under half (42% - 44 victims) of all victims of Family and Domestic Violence-related homicides.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare's Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010-11 to 2018-19 (2021)42 found that around 29,000 people had at least one FDV hospital stay from 2010–11 to 2017–18. Of these, 1 in 3 were male (32%).

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2017 (2018)31 found that in 2017, males comprised just under half (43% - 54 victims) of all victims of Family and Domestic Violence-related Murders (Table 22).

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2016 (2017)29 is the largest and most recent survey of violence in Australia. It found that:

- DURING THE LAST 12 MONTHS30

- Over 1 in 3 persons who experienced violence from an intimate partner were male (35.3%)

- Almost 1 in 3 persons who experienced violence from a cohabiting partner were male (32.7%)

- Almost 2 in 5 persons who experienced violence from a current partner were male (39.9%)

- Over 1 in 3 persons who experienced violence from a boyfriend/girlfriend or date were male (34.3%)

- Almost 1 in 5 persons who experienced violence from a previous partner were male (18.8%)

- Almost half the persons who experienced violence from a known person were male (45.5%)

- Almost half the persons who experienced emotional abuse by a partner were male (45.8%) (47.7% of persons who experienced it by a current partner and 43.4% by a previous partner)

- Almost half of these males experienced anxiety or fear due to the emotional abuse (41.4% of males who experienced current partner abuse and 43.1% of males who experienced previous partner abuse)

- 13.8% of men that experienced emotional abuse by a current partner had their partner deprive them of basic needs such as food, shelter, sleep, or assistive aids, compared to 6.4% of women.

- 8.9% of men that experienced emotional abuse by a current partner had their partner threaten to take their child/ren away from them, compared to 4.6% of women.

- 38.5% of men that experienced emotional abuse by a previous partner had their partner lie to their child/ren with the intent of turning them against them, compared to 25.1% of women.

- 7.3% of men that experienced emotional abuse by a current partner had their partner lie to other family members or friends with the intent of turning them against them, compared to 6.6% of women.

- 10.1% of men that experienced current partner emotional abuse had their current partner keep track of where they were and who they were with, compared to 9.9% of women.

- Over 1 in 3 persons who experienced sexual harassment were male (34.0%). Most males who experienced sexual harrassment were harassed by a female perpetrator (72.2% were harassed by a female while 48.2% were harassed by a male).

- The largest category of increase in sexual harassment between 2012 and 2016 was in males harassed by a female perpetrator, which rose by a massive 67.5%. Females harassed by a male perpetrator rose by 15% during the same period.

- Over 1 in 3 persons who experienced stalking were male (35.0%). Most males who experienced stalking were stalked by a male perpetrator (68.9% were stalked by a male while 36.3% were stalked by a female).

- Almost 1 in 3 persons who experienced sexual assault were male (28.4%). Most males who experienced sexual violence were assaulted or threatened by a female perpetrator (82.9%).

- 6 per cent of all males experienced violence compared to 4.7% of all females.

- The majority of men that experienced intimate partner violence experienced it by a female perpetrator (93.6%). The remainder were in same-sex relationships with male perpetrators.

- SINCE THE AGE OF 15

- Men were 2 to 3 times more likely than women to have never told anybody about experiencing partner violence, around 50% more likely than women to have never sought advice or support about experiencing partner violence, almost 20% more likely than women to have not contacted police about experiencing partner violence, and less than half as likely as women to have had a restraining order issued against the perpetrator of previous partner violence.

- AFTER FINAL SEPARATION FROM VIOLENT PREVIOUS PARTNER

- Male victims were more than twice as likely to report 'sleeping rough' (e.g. on the street, in a car, in a tent, squatting in an abandoned building) after finally separating from their violent previous partner compared with female victims (4.7% vs 1.9%) and less than half as likely to report having stayed in a refuge or shelter (2.4% vs 5.1%).

The previous edition of this survey, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2012 (2013)1 also found that:

- one in three victims of current partner violence during the last 12 months (33.3%) and since the age of 15 (33.5%) were male

- more than one in three victims of emotional abuse by a partner during the last 12 months (37.1%) and since the age of 15 (36.3%) were male. Around half of these men experienced anxiety or fear due to the abuse

- at least one in three victims of stalking during the last 12 months (34.2%) were male

- around one in three victims of physical violence by a boyfriend/girlfriend or date since the age of 15 (32.1%) were male

- almost one in three victims of sexual assault during the last 12 months (29.6%) were male

- more than one in three victims of physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 15 (39.0%) were male

- the rate of men reporting current partner violence since the age of 15 almost doubled (a rise of 175%) since 2005 (an estimated 119,600 men reported such violence in 2012)

- the rate of men reporting dating violence since the age of 15 also rose by 140% since the 2005 survey

- the rate of men reporting current partner violence in the 12 months prior to interview quadrupled (a rise of 394%), however these estimates are considered too unreliable for general use because of the small number of men interviewed for the 2005 survey (the ABS surveyed 11,800 females but only 4,500 males in 2005 - a sampling gender bias that worsened in the 2012 survey, where only 22% of respondents were male)

- the vast majority of perpetrators of dating and partner violence against men were female - only 6 or 7% of incidents involved same-sex violence

- men were less than half as likely as women to have told anybody about partner violence, to have sought advice or support, or to have contacted the police.

An earlier edition of this survey, 4906.0 - Personal Safety, Australia, 2005 (Reissue) (2006)2 also found that:

- 29.8% (almost one in three) victims of current partner violence since the age of 15 were male

- 24.4% (almost one in four) victims of previous partner violence since the age of 15 were male

- 29.4% (almost one in three) victims of sexual assault* during the last 12 months were male

- 26.1% (more than one in four) victims of sexual abuse* before the age of 15 were male

Males make up around one third of persons applying for protection orders in the three largest states of Australia. In NSW34, the number of persons protected by Domestic Apprehended Violence Orders issued April 2019 to March 2020 were male 14,139 (31%) and female 31,179 (69%). In Victoria35, affected family members on original FVIO applications 2018 to 2019 were male 21,006 (36%) and female 37,041 (64%). In Queensland36, applications lodged: gender of aggrieved, 2019 to 2020 year to date were male 6,932 (27%) Female 19,186 (73%).

The Victorian Royal Commission Into Family Violence (2015)37 found that "Over the five years from July 2009, the proportion of male victims has increased and in 2013-14 male victims made up 31% (n=5,052) of total victims of family violence." It also found that, over the same period, there were more male than female victims in the age groups 0-14 years and 65 years and over.

As part of their evaluation of the 2012 family violence amendments, the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) found in their Experiences of Separated Parents Study (2015)25 that males (fathers) made up:

- 41.3% of parents who reported experiencing physical hurt (with or without emotional abuse) before/during separation

- 51.8% of parents who reported experiencing emotional abuse alone before/during separation. In 2 out of 11 types of emotional abuse, fathers reported experiencing abuse “often” at equal or higher rates than mothers.

- 34.6% of parents who reported experiencing between 21 and 55 incidents of emotional abuse before/during separation, and 45.5% of parents who reported between 11 and 20 incidents

- 42.6% of parents who reported experiencing the highest levels of severity of fear (9 or 10 on a 10-point scale) before/during separation, 43.5% of parents who reported experiencing the most severe control, and 44.6% of parents who reported experiencing the most severe coersion

- 45.5% of parents who reported experiencing physical hurt since separation

- 47.4% of parents who reported experiencing emotional abuse (with or without physical hurt) since separation. In 4 out of 13 types of emotional abuse, fathers reported experiencing abuse at equal or higher rates than mothers. In 7 out of 11 types of emotional abuse, fathers reported experiencing abuse “often” at equal or higher rates than mothers.

- 41.2% of parents who reported experiencing between 21 and 55 incidents of emotional abuse since separation, and 47.2% of parents who reported between 11 and 20 incidents

- 46.5% of parents who reported often feeling fearful after physical violence since separation, and 48.1% after emotional abuse alone

- 57.3% of parents who reported often feeling controlled after physical violence since separation, and 59.5% after emotional abuse alone

- 57.4% of parents who reported often feeling coerced after physical violence since separation, and 60.5% after emotional abuse alone

- 51.7% of parents who reported experiencing the highest levels of severity of fear (9 or 10 on a 10-point scale) since separation, 60.5% of parents who reported experiencing the most severe control, and 57.6% of parents who reported experiencing the most severe coersion.

There was no statistically significant difference between fathers and mothers in the frequency of reporting having often felt fearful after experiencing physical violence or emotional abuse since separation, and fathers were statistically significantly more likely than mothers to report having often felt controlled or coerced after experiencing physical violence or emotional abuse since separation. When it came to severity, fathers were also more likely than mothers to report experiencing the highest level of fear, control and coersion (10 on a 10-point scale) that they felt arising from the focus parent’s behaviour since separation. Experiences of control and coersion were statistically significantly higher for fathers than mothers.

The Queensland Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board’s 2017–18 Annual Report33 found that there were more recorded intimate partner homicides involving male deceased than female deceased, for the first time. There were 8 male and 4 female victims of intimate partner homicide in Queensland in 2017-18.

Research by Ahmadabadi et al in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence (2017) has found that males more often remain in an abusive relationship and report experiencing higher rates of intimate partner violence in their current relationships compared with females. The paper, Gender Differences in Intimate Partner Violence in Current and Prior Relationships32, adds to the growing research literature supporting a gender symmetry model of family violence.

Researchers at Deakin University investigating Alcohol/Drug-Involved Family Violence in Australia (2016)27 surveyed a representative sample of 5,118 Australians and found that males accounted for between 11% and 37% of victims in incidents attended by police, 24% of intimate partner violence victims and 34% of family violence victims in the panel survey. It also found that "there were no significant differences in the proportion of male and female respondents classified as engaging in no, low, and high Coercive Controlling Behaviours (ps > 0.05)."

The NSW Domestic Violence Death Review Team (2017)38 found that males made up 44% of persons who committed suicide between 1 July and 31 December 2013 who were known to Police as victims of intimate partner and/or family violence:

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2014 EXPERIMENTAL FAMILY AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE STATISTICS (2015)26 showed that males made up between 20% (one in five) and 32% (one in three) reported victims of family and domestic violence-related assault, depending on the state or territory surveyed. Overall, for the 5 states and territories surveyed (SA, NT, WA, ACT, NSW), males made up 28.3% of victims (almost one in three).

The Anglicare WA Community Perceptions Report 2014: Family And Domestic Violence21 found that between 18 per cent and over 50 per cent of victims of domestic and family violence were male, depending on the kinds of violent and abusive behaviours surveyed.

Percentage of victims that were male for different behaviours:

- Isolating behaviours - over 50% (exact figures not published)

- Shamed on social media - over 50% (exact figures not published)

- Being pushed, slapped, punched, choked or kicked - 42.6%

- Being induced to physical or emotional exhaustion - 41.0%

- Mind games and manipulation - 41.0%

- Being stalked or followed - 35.7%

- Forced sexual contact or coercion - 18.2%

The report also found that between 14 per cent and 35 per cent of perpetrators of domestic and family violence were female, depending on the kinds of violent and abusive behaviours surveyed.

Percentage of perpetrators that were female for different behaviours:

- Threats, put-downs, insults or shouting at someone - 35.0%

- Belittling someone’s views or opinions- 32.0%

- Verbally shaming, humiliating or degrading someone - 23.5%

- Being overly critical of daily things - 23.1%

- Threatening physical violence or harm - 22.2%

- Played mind games on another - 14.3%

The SA Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Survey (1999)3 found that:

- 32.3% (almost one in three) victims of reported domestic violence by a current or ex-partner (including both physical and emotional violence and abuse) were male

- 19.3% (almost one in five) victims of attempted or actual forced sexual activity* since they turned 18 years of age were male (excluding activity from partners or ex-partners).

Both this survey and the Personal Safety Survey excluded the male prison population where over one quarter of young inmates experience sexual assault*4.

The Crime Prevention Survey (2001)5 surveyed young people aged 12 to 20 and found that:

- while 23% of young people were aware of domestic violence against their mothers or step-mothers by their fathers or step-fathers, an almost identical proportion (22%) of young people were aware of domestic violence against their fathers or step-fathers by their mothers or step-mothers

- an almost identical proportion of young females (16%) and young males (15%) answered “yes” to the statement “I’ve experienced domestic violence”

- an almost identical proportion of young females (6%) and young males (5%) answered “yes” to the statement “my boyfriend/girlfriend physically forced me to have sex”

- More stats here.

The NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2005)6 found that 28.9% (almost one in three) victims of domestic assault between 1997 and 2004 were male. Male and female victims received very similar numbers and types of injuries (see figures 1 and 2 below). The latest (2014)18 figures show that 31.2% (almost one in three) victims of assault - domestic violence related offences recorded by NSW Police were male.

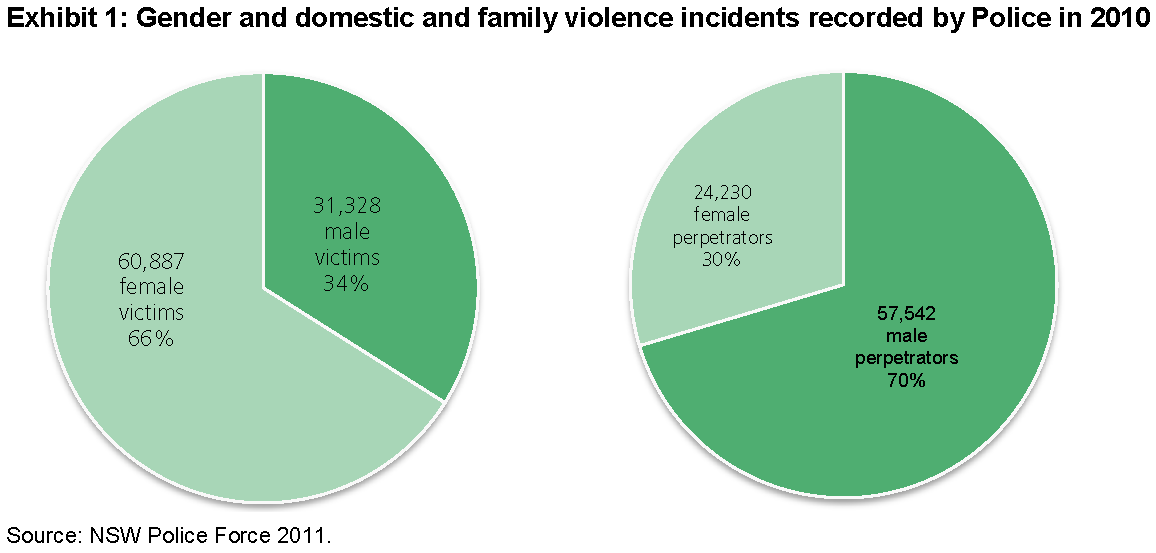

The NSW Auditor General19 found that 34% (more than one in three) domestic and family violence incidents recorded by Police in 2010 involved male victims and 30% (almost one in three) involved female perpetrators.

The first year of the Safer Pathway trial scheme at Waverley and Orange (NSW) (2015) saw 1,758 male and 4,180 female victims of domestic violence referred to the sites. Almost one in three victims (29.6%) were male24 .

Queensland Police statistics22 obtained in May 2015 via the Queensland Government Statistician's Office show that 27.7% (almost one in three) reported victims of offences against the person in 2013-14 in a family/domestic context were male. These numbers are not based on complaints, but actual cases where the police have taken action.

The Queensland Crime and Misconduct Commission (2005)7 found that 32.6% (almost one in three) victims of family violence reported to police were male.

The Australian Institute of Criminology (2021)8 found that 38% (almost two in five) victims of domestic homicide and 27% (more than one in four) victims of intimate partner homicide between 2018-2019 were male:

SBS News, in collaboration with the Australian Institute of Criminology, published an overview of all victims of domestic or family homicide over the 23 year period 1989/90 to 2011/12. They found that 408 male partners (24.8%) and 1237 female partners (75.2%) had been killed during this period.

The Victoria Police Law Enforcement Assistance Program (2017)28 found there were 15,423 male and 38,688 female affected family members in family violence incidents during the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2016 (28.5% - almost one in three - were male).

The Victorian Victims Support Agency (2012)9 found that in 2009-10, 36% (more than one in three) persons admitted to Victorian Public Hospitals for family violence injuries were male.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017)20 found that 29.6% (almost one in three) victims of hospitalised family violence (from a spouse or domestic partner, parent or other family member) in Australia from 1999–00 to 2012–13 were male. There were extraordinarily high numbers of males (8,708) compared to females (1,580) where no perpetrator type was recorded. It is likely that more data is captured for female injury victims because of the compulsory domestic violence screening programs in place for women only in hospitals across Australia. The male reticence to name the perpetrator of injury when it is an intimate partner also probably plays a part.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies (1999)10 observed that, post-separation, fairly similar proportions of men (55%) and women (62%) reported experiencing physical violence including threats by their former spouse. Emotional abuse was reported by 84% of women and 75% of men.

A University of Melbourne / La Trobe University study (1999)11 found that men were just as likely to report being physically assaulted by their partners as women. Further, women and men were about equally likely to admit being violent themselves. Men and women also reported experiencing about the same levels of pain and need for medical attention resulting from domestic violence.

An extensive study of dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations by Murray Straus (2008)12 found that, in Australia, 14% of physical violence between dating partners during the previous 12 months was perpetrated by males only, 21% by females only and 64.9% was mutual violence (where both partners used violence against each other).

Fergusson & Mullen (1999)13, in Childhood sexual abuse: an evidence based perspective, found that one in three victims of childhood sexual abuse* were male.

The Queensland Government Department of Communities (2009)14 reported that 40% (more than one in three) domestic and family violence protection orders issued by the Magistrate Court were issued to protect males.

A study of risk factors for recent domestic physical assault in patients presenting to the emergency department of Adelaide hospitals (2004)15 found that 7% of male patients and 10% of female patients had experienced domestic physical assault. This finding shows that over one in three victims were male (39.7%).

The Australian Institute of Family Studies’ evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms (2009)16 found that 39% (more than one in three) victims of physical hurt before separation were male; and 48% (almost one in two) victims of emotional abuse before or during separation were male.

A study of relationship aggression, violence and self-regulation in Australian newlywed couples by researchers at the University of Queensland (2009)17 found that a substantial minority of couples reported violence, with 82 couples (22%) reporting at least one act of violence in the last year (i.e., the year leading up to and including their wedding). Female violence was more common than male violence, with 76 women (20%) and 34 men (9%) reported to have been violent. There was a significant association between female and male violence. In violent couples the most common pattern was for only the woman to be violent (n=48/82 or 59% of violent couples), next most common was violence by both partners (n=28, 34%), and least common was male-only violence (n=6, 7%).

Halford et al conducted Australian research in 201123 on intimate partner violence (IPV) in couples seeking relationship education for the transition to parenthood and found that in 19% of couples both partners perpetrated IPV, in 12% only the woman had perpetrated IPV, and in 3% only the man had perpetrated IPV.

These authoritative sources agree that at least one in three victims of family violence is male. Yet governments have been unable to acknowledge or offer appropriate services for these victims. The Australian Government’s human rights obligations require it to cater equitably for the needs of all, regardless of gender. It is time to care for all those in need, whether female or male.

References

1 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2013, Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2012, cat no 4906.0, ABS, Canberra. www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.ns...mf/4906.0. Significant problems with this survey include, (a) only female interviewers were used, and (b) a much smaller sample of male informants was used compared to female informants.

2 Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006, Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2005, cat no 4906.0, ABS, Canberra. www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/...abs@.nsf. Significant problems with this survey include, (a) only female interviewers were used, (b) a much smaller sample of male informants was used compared to female informants, and (c) no data was published on types of violence or injuries or threats received by male victims.

3 Dal Grande, E, Woollacott, T, Taylor, A, Starr, G, Anastassiadis, K, Ben-Tovim, D, Westhorp, G, Hetzel, D, Sawyer, M, Cripps, D, and Goulding, S. 1999, Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Survey, September 1999, Epidemiology Branch, South Australian Department of Human Services, Adelaide. web.archive.org/...survey.pdf

4 Heilpern, D. (2005). Sexual assault of prisoners: Reflections. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 28(1), 286-292. Retrieved November 1, 2009, from classic.austlii.edu.au/...2005/17.html

5 Crime Research Centre (University of Western Australia) and Donovan Research 2001, Young people and domestic violence – national research on young people’s attitudes to and experiences of domestic violence, National Crime Prevention, Canberra. www.oneinthree.com.au/ypdv

6 People, J. 2005, ‘Trends and Patterns in Domestic Violence Assaults’, Crime and Justice Bulletin, No 89, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, October. www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/...cjb89.pdf

7 Crime and Misconduct Commission (2005, March). Policing Domestic Violence In Queensland: Meeting the Challenges. Brisbane: Crime and Misconduct Commission. www.ccc.qld.gov.au/...challenges

8 Bricknell, S. & Doherty, L. (2021). Homicide in Australia 2018-19. Statistical Report no. 34. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. www.aic.gov.au/publi...sr34.

9 Victims Support Agency (2012). Victorian Family Violence Database Volume 5: Eleven-year Trend Report. Melbourne: Victorian Government Department of Justice. Retrieved September 17, 2012, from www.justice.vic.gov.au/...-volume-5

10 Wolcott, I., & Hughes, J. (1999). Towards understanding the reasons for divorce. Australian Institute of Family Studies, Working Paper, 20. Retrieved November 1, 2009, from aifs.gov.au/...-divorce

11 Heady, B, Scott, D, & de Vaus, D, 1999. Domestic Violence in Australia: Are Women and Men Equally Violent?, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, Melbourne. fact.on.ca/I...heady99.pdf

12 Straus, M, 2008, Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations, Children and Youth Services Review 30, 252–275. oneinthree.com.au/...004.pdf

13 Fergusson, D. M., & Mullen, P. E. (1999). Childhood sexual abuse: An evidence based perspective. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.

14 Queensland Government Department of Communities (2009, October 9). Domestic and family violence orders: Number and type of order by gender, Queensland, 2004-05 to 2008-09. [Letter]. Retrieved October 31, 2009, from www.menshealthaustralia.net/files/Ma...DVOs.pdf

15 Stuart, P. (2004). Risk factors for recent domestic physical assault in patients presenting to the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 16(3), 216-224. oneinthree.com.au/...400590x.pdf

16 Kaspiew, R., Gray, M., Weston, R., Moloney, L., Hand, K., & Qu, L. (2009, December). Evaluation of the 2006 family law reforms. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved July 5, 2010, from www.aifs.gov.au/instit...eport.pdf

17 Halford, W.K., Farrugia, C., Lizzio, A. & Wilson, K. (2010) 'Relationship aggression, violence and self-regulation in Australian newlywed couples', Australian Journal of Psychology, 62: 2, 82 — 92, First published on: 19 May 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2011, from dx.doi.org/10...0902804169.

18 Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2014). NSW Recorded Crime Statistics 2014 (Excel spreadsheet). Retrieved November 8, 2015, from www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/P...014.aspx.

19 Audit Office of New South Wales (2011). New South Wales Auditor-General's Report: Responding to Domestic and Family Violence, Performance Audit. Retrieved May 17, 2013, from www.audit.nsw.gov.au/s...ence.pdf.

20 AIHW: Pointer S (2015). Trends in hospitalised injury, Australia: 1999–00 to 2012–13. Injury research and statistics series no. 95. Cat. no. INJCAT 171. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved Novenber 2, 2017 from www.aihw.gov.au/r...summary

21 Cooke, T. & Nangle, D. (2014). Community Perceptions Report 2014: Family And Domestic Violence. East Perth: Anglicare WA. Retrieved October 27, 2014, fromwww.anglicarewa.org.au/th...EAD.pdf

22 Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (2015, May 13). Reported victims of offences against the person in 2013-14, Queensland. [Email]. Retrieved May 16, 2015, from www.oneinth...tats.pdf

23 Halford, W. K., Petch, J., Creedy, D. K., & Gamble, J. (2011). Intimate partner violence in couples seeking relationship education for the transition to parenthood. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 10(2), 152-168. oneinthree.com.au/s...562835.pdf

24 Partridge, E. (2015). Statistics Reveal Hidden Violence. Sydney Morning Herald, September 26-27, 2015, p6. Retrieved October 11th, 2015, from http://www.oneinthree.com.au/s/Sta...olence.pdf.

25 Kaspiew, R., Carson, R., Dunstan, J., De Maio, J., Moore, S., Moloney, L. et al. (2015). Experiences of Separated Parents Study (Evaluation of the 2012 Family Violence Amendments). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.. Retrieved April 29th, 2018, from aifs.gov.au/...-study

26 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015), Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2014, cat no 4510.0, ABS, Canberra. Retrieved July 1st, 2016 from www.abs.gov.au/...00.

27 Miller, P, et al (2016), Alcohol/Drug-Involved Family Violence in Australia (ADIVA) Final Report, Deakin University. Retrieved December 8th, 2016 from www.oneinthree.com.au/s/A...Report.pdf.

28 Crime Statistics Agency Victoria (2017), Victoria Police Law Enforcement Assistance Program. Retrieved November 2nd, 2017 from www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/...ice.

29 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017). Personal Safety Survey, Australia, 2016 (Cat. No. 4906.0). Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved November 8th, 2017 from www.abs.gov.au/auss...06.0.

30 Some of these estimates have Relative Standard Errors (RSEs) of greater than 25% and should be used with caution due to the relatively small number of males surveyed by the ABS. Please see our infographic for further details.

31 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). 4510.0 - Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2017. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved December 23rd, 2018 from abs.gov.au/AUSSTA...ument

32 Ahmadabadi, Z., Najman, J. M., Williams, G. M., Clavarino, A. M., & d’Abbs, P. (2017). Gender Differences in Intimate Partner Violence in Current and Prior Relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Retrieved May 6th, 2019 from journals.sagepub.com/...30563

33 Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board (2018). Domestic and Family Violence Death Review and Advisory Board 2017–18 Annual Report. Retrieved July 3rd, 2019 from www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Docu...6-MwZCNw

34 NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2020). Apprehended Violence Orders Excel Table. Sydney: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Pa...rders-.aspx

35 Crime Statistics Agency (2020). Magistrates’ Court data dashboard. Melbourne: Crime Statistics Agency. (Crime Statistics Agency Victoria) www.crimestatistics.vic.gov.au/fam...es-court

36 Queensland Courts (2020). Queensland Courts’ domestic and family violence (DFV) statistics. Brisbane: The State of Queensland (Queensland Courts). (Queensland Courts’ domestic and family violence statistics) www.courts.qld.gov.au/c...lic/stats

37 State of Victoria, Royal Commission into Family Violence: Summary and recommendations, Parl Paper No 132 (2014–16). rcfv.archive.roya...ons.html

38 Domestic Violence Death Review Team, NSW Domestic Violence Death Review Team Report 2015-2017. Camperdown: Domestic Violence Death Review Team. www.coroners.nsw.gov.au/co...iew.html

39 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022). Recorded Crime - Victims, Australia, 2021. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved October 19th, 2022 from www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/recorded-crime-victims/latest-release#victims-of-family-and-domestic-violence-related-offences

40 Fitz-Gibbon, K., Meyer, S., Maher, J., & Roberts, S. (2022). Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts (Research report, 15/2022). ANROWS, Sydney. Retrieved October 21st, 2022 from www.anrows.org.au/publication/adolescent-family-violence-in-australia-a-national-study-of-prevalence-history-of-childhood-victimisation-and-impacts/

41 NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (2023). NSW Crime Tool: Incidents of Assault (Domestic assault) from January 2021 to December 2022. BOCSAR, Sydney. Retrieved March 5th, 2023 from crimetool.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/bocsar/

42 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021). Examination of hospital stays due to family and domestic violence 2010-11 to 2018-19. Cat. no. FDV 9. Canberra: AIHW. Retrieved August 7th, 2023 from www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/examination-of-hospital-stays-due-to-family-and-do/summary

43 Australian Bureau of Statistics (2023). Recorded Crime - Victims, 2022. Canberra: ABS. Retrieved August 13th, 2023 from www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/recorded-crime-victims/latest-release#victims-of-family-and-domestic-violence-related-offences

44 Mathews, B., Hegarty, K.L., MacMillan, H.L., Madzoska, M., Erskine, H.E., Pacella, R., Scott, J.G., Thomas, H., Meinck, F., Higgins, D., Lawrence, D.M., Haslam, D., Roetman, S., Malacova, E. & Cubitt, T. (2025). The prevalence of intimate partner violence in Australia: A national survey. The Medical Journal of Australia, pp. 1-9. www.mja.com.au/journal/2025/222/9/prevalence-intimate-partner-violence-australia-national-survey#

45 O’Donnell, K., Woldegiorgis, M., Gasser, C., Scurrah, K., Andersson, C., McKay, H., Hegarty, K., Seidler, Z., & Martin, S. (2025). The use of intimate partner violence among Australian men. Insights #3, Chapter 1. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved June 5th, 2025 from aifs.gov.au/tentomen/insights-report/use-intimate-partner-violence-among-australian-men